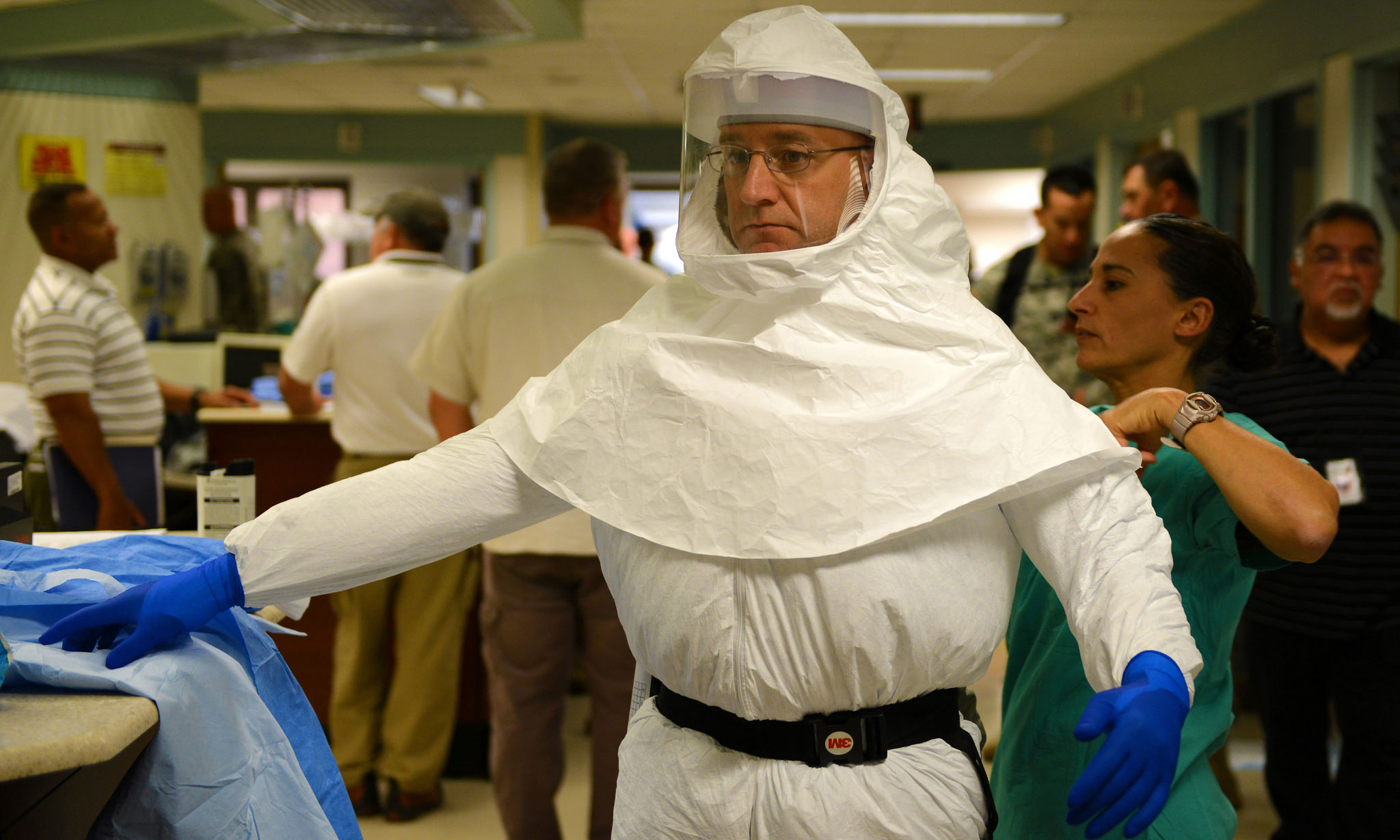

In covering the recent Ebola outbreak at a local hospital, The Dallas Morning News was so cautious that it was occasionally late on big stories — it was among the last news outlets to publicly identify the two Dallas nurses who contracted the disease – even though the paper knew both victims’ names.

But that was by design.

“We have been very careful to follow that maxim that we’d rather be right than first,” said David Duitch, editor of Dallasnews.com, the newspaper’s website.

Caution has been a cornerstone of the company’s digital media strategy as it covered the disease in Dallas, according to Duitch and Robert Wilonsky, digital managing editor for The Dallas Morning News. The website editors opted to wait to release news developments on Ebola until they received confirmation from their own sources, even as the paper was experiencing a rapid increase in website traffic and social media followers during what became a big, fast-moving news story in their backyard.

“We understand the responsibility that comes with the digital side of things,” Wilonsky said. “Because yeah, you can go back and correct it quickly, but man, God forbid you put out one wrong tweet, one wrong fact, one wrong piece of information on a story like this. Because God forbid people stop trusting you, and when you report something really important you don’t want them to taste that grain of salt with it.”

The paper’s editors said telling the stories of the Ebola cases required an abundance of caution.

That’s why Wilonsky said the paper was among the last to reveal the name of Amber Vinson, who cared for Thomas Eric Duncan, the first person diagnosed in the U.S. with the disease. The paper was also slow to name Nina Pham, the Dallas nurse who was the first person to contract the disease in the United States, Wilonsky said. (Pham and Vinson were both recently declared free of Ebola.)

“We were, in fact, the last – especially I want to say in Amber Vinson’s case, I remember that for sure – we were the last to report her name even though we had her name,” Wilonsky said.

They waited to publish Vinson’s name in deference to the patient’s privacy.

As Wilonsky told it, holding off on publishing the nurse’s name was a case of giving Vinson the same treatment he would have wanted. Even after other outlets reported the name, Wilonsky said the staff waited to publish it until they could confirm it with the family.

“You have to ask yourself, ‘if I was in her spot what would I want?’” Wilonsky said.

Other Examples of Caution

When the paper published a 600-word profile on Oct. 12 on Pham – complete with quotes from friends and personal details — they didn’t include her name. That’s because hospital staff had not confirmed her identity at the time of publication.

“Her family would not comment,” according to the story. “The Dallas Morning News identified her through public records, social media sites, a state nursing database and interviews but is not publishing her name because hospital officials have not confirmed it.”

Other news outlets followed a similar method, said Keith Campbell, managing editor of The Dallas Morning News.

The paper also was careful in its decision to publish Duncan’s name.

Texas Presbyterian Hospital of Dallas announced Duncan had tested positive for Ebola on Sept. 30 — but the patient’s name had not yet been released.

The Dallas Morning News waited to publish Duncan’s name for the first time on Oct. 2, Campbell said. At that point, he said Duncan’s name was “in the public domain.”

This hesitance to rush stories to publication on the website was also done in reverence to the privacy of the patients, the editors said.

The Dallas Morning News waited to release the patients’ names until the paper could confirm their identities.

In the case of Pham, Campbell said this meant the paper verifying her identity through “trusting sources who were extremely close to her.”

Changes in Coverage

While the paper didn’t change its editorial process or institute a new policy to cope with coverage of the Ebola cases, Wilonsky and Duitch both emphasized The Dallas Morning News’ choice to value accuracy over speed for stories related to the disease.

“This is the most important story of the year for us – of a long time,” Wilonsky said. “It’s a significant story that’s going to have long term ramifications for hundreds of thousands of people well outside of Dallas, Texas. We want to get it right.”

For example, the paper took a measured approach when it published a post on reports that a woman became sick at a train station, resulting in its closing.

The paper was careful not to say conclusively that she was being monitored for Ebola, as another local news organization reported, Duitch said.

In the original post, the paper pointed out that another station had reported the “individual was being monitored for possible exposure to the Ebola virus.”

But it added that transportation officials were reporting something different.

“DART officials, however, said the individual reportedly lived in the same apartment complex as Thomas Eric Duncan, the Liberian man who died earlier this month after contracting Ebola,” the paper reported.

The paper later updated that statement too; transportation officials retracted it and said the woman had merely stayed there some time ago for a few days.

Ultimately it came out that the woman was not on the Ebola watch list and there was no cause for concern.

Social Media and Ebola

Readers generally responded positively to the paper’s coverage of the disease, Duitch said, although he admitted that at a certain point the sheer amount of content caused Ebola “fatigue” among the public.

Whatever the reader reaction, the site has seen a spike in traffic.

Dallasnews.com has seen a 150 percent increase in unique visitors and doubled its page views since the first story about Ebola in Dallas broke in late September, Duitch said.

The site’s Twitter account has gained 9,743 followers since Duncan tested positive – more than 1,000 more followers than the account added the month before, according to data from twittercounter.com.

A large portion of the website’s traffic is coming through The Dallas Morning News’ social media accounts as well, Duitch said.

Part of The Dallas Morning News’ social media strategy has involved Dr. Seema Yasmin, a former epidemiologist for the Centers for Disease Control who is now a staff writer with The Dallas Morning News and a professor at the University of Texas at Dallas.

Yasmin answered questions from her personal Twitter account in chats that were also posted on the Ebola landing page of Dallasnews.com. She also appeared in several videos embedded on a special page within the Ebola coverage section of the website to help assuage concerns about the disease and its possible spread.

For example, in one video she let readers know that Ebola is not as easily spread as airborne illnesses like the common cold or flu.

“We get far more questions than she can answer in the time allotted,” Duitch said. “So throughout the day and days after a Twitter chat she will try to go back online and answer some of those questions.”

Leave a Comment