The Yo app has received its fair share of ridicule.

But I always say: don’t hate it ‘til you try it.

So I tried it.

I spent about a week experimenting with Yo, the app that lets you send the word “Yo” to your contacts. It shows up as a push notification along with an audible “Yo” that sounds more like a demon beckoning lost souls than a friendly conversation starter.

And that’s all it does.

At least, it was, until the newest update, released on Aug. 12, that allows Yo users to send links and hashtags as well. Now Yo users can promote content.

I started using the app when I wrote a story about how news organizations are using Yo to promote their stories.

At first I only had my editor added on Yo, and we would only send Yos as a joke. It all changed, however, when I sent my editor a Yo (along with a text explaining the Yo) to let her know that my story was ready to be edited.

She sent me a Yo back when the story was edited.

And thus, the app evolved from a useless gimmick into a highly efficient secret code.

Soon it was understood that a Yo from me means “Yo. Look at my story,” and a Yo from my editor means “Yo. I looked at your story.” This little code was a little faster than texting and got the job done just as well. The app, surprisingly, had earned its place in the office.

As I discovered earlier, news organizations such as the Wall Street Journal and Nieman Journalism Lab are using the app.

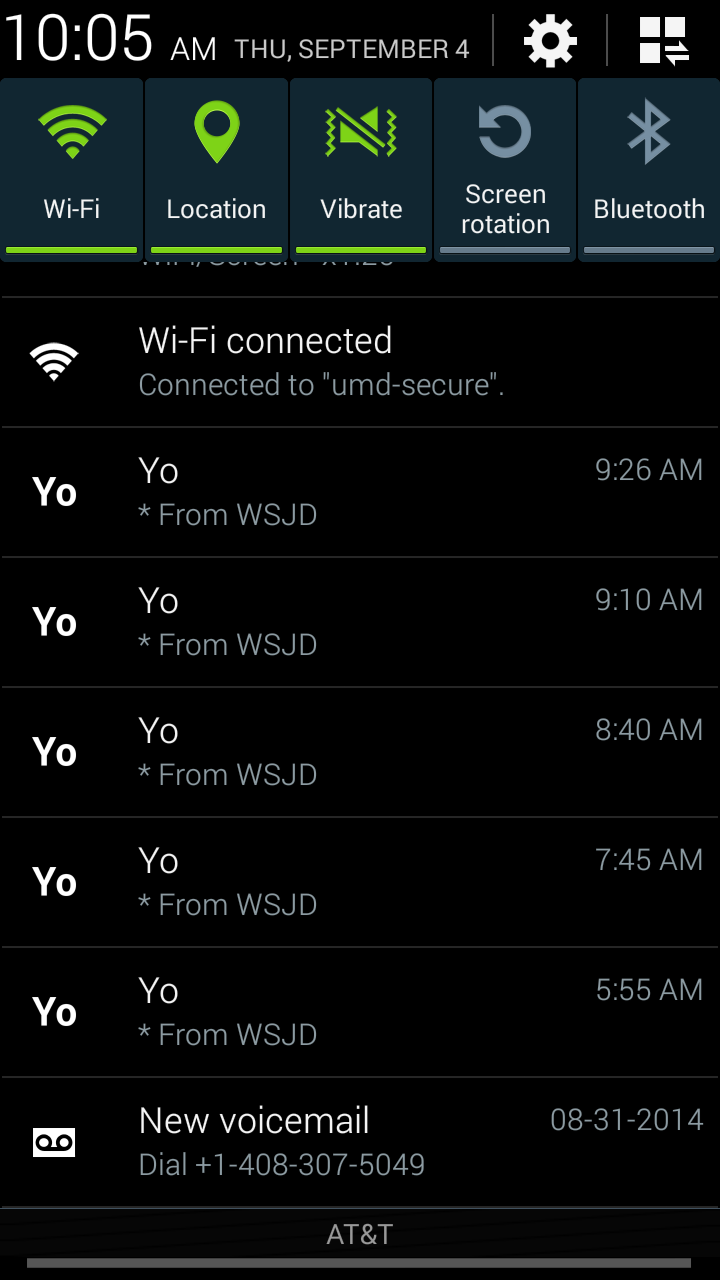

The Wall Street Journal has sent out its fair share of Yos. In one 24-hour period, I received 21 Yos from The Wall Street Journal, including ones at 1 and 5 a.m. As much as I like being awoken in the middle of the night for no reason whatsoever, it got old. Fast.

It would have gotten annoying even if I were interested in all the articles. But the problem is they aren’t articles about any particular subject. The Wall Street Journal simply sends out a Yo every time a new story is published. And that’s a lot of Yos.

The Wall Street Journal did not respond to requests for comment.

There are some novel uses for Yo as well. I followed RAINHOUR, which sends me a Yo every time it’s about to rain within the hour in my town. LARGEEARTHQUAKE sends a Yo every time there is an earthquake greater than 6.0 in magnitude anywhere in the world.

Or Arbel, co-founder and CEO of Yo, has big visions for the future of Yo.

“Why can’t we get a Yo from McDonald’s when the food is ready or from Starbucks when the coffee is ready?” he asked.

Arbel said he sees a world where Yo users are able to subscribe to a cornucopia of businesses all through the same app. They will be able to get a Yo from a restaurant when the table is ready, or from The New York Times when a particular article is published.

According to TechCrunch, the Yo app is “thriving,” with about 1.5 million active users and 15 YPS (Yos per second) sent. This may be down from their unprecedented 100 YPS over the summer, but keep in mind, this is “three months after all of the hype.”

But how does it perform in the social sphere? How are people using it?

I tried to get my friends at the University of Maryland to use the app so we could Yo at each other and see what it was all about. They weren’t having it.

Most scoffed at the idea of the simplistic app, questioning its limitations.

“I think it’s stupid,” said Sumouni Basu, a junior bio-engineering major.

“I think it’s useless,” said Camilla Thompson, a junior animal science major.

“It’s so dumb, I can’t emphasize that enough,” said Cadeem Franklin, a sophomore mechanical engineering major. “I don’t see any practical use and I don’t see it lasting more than a month.”

Even after we downloaded the app, we found that text messages did the job better every time. The problem is the Yo app isn’t much faster than texting; you still have to open the app and tap on somebody’s name.

In addition, the fact that many of the Yos had to be accompanied by text messages to explain what the Yo was for (i.e. Want to get lunch?) makes the app seem superfluous at times.

“I think anything you can do with Yo, you can do better with texting,” said Thompson.

After asking around, I only found students who use Yo as a joke.

“We’ve only ever used it satirically,” said Josh Sheldon, sophomore mechanical engineering major. Sheldon used the app last summer with his roommates, Joshua Hall and Matthew Hahne.

“I would attempt to Yo as much as possible,” said Hall, a sophomore broadcast journalism major.

It should be noted that this act does not make Hall very popular.

As he said that, Hall took out his phone and began to Yo his roommate, Sheldon, who was sitting right next to him, at a speed that would make Lightning McQueen jealous. Sheldon Yo’d back. Soon, the room was filled with a cacophony of metallic voices.

“I use the app only to annoy people,” said Thompson, who repeatedly sent me strings of Yos that would make my phone blow up with notifications. It nearly ruined our friendship.

But what would students change about the app? Nothing really can be changed, it turns out.

“Since there’s so little functionality, anything that would be a tweak for a bigger system would turn it into something else entirely,” said Hahne, a sophomore mechanical engineering major.

Still, some think the app has potential if implemented in the right way.

Basu imagines uses for it in emergency situations.

“It could be useful in weather emergencies or domestic violence, in situations of immediate concern where you can’t call the police but you need help,” she said.

Thompson, on the other hand, thinks that “Yo” is the wrong word for the app.

“Maybe if they had a ‘Screw You’ app, I would use it,” said Thompson. “That might get popular.”

Leave a Comment