At any gathering of newspaper veterans of a certain age – and many of them are at funerals nowadays – you’ll hear simultaneous laments for the “golden age” of newspapers and self-congratulations for having been lucky enough to have been a part of it.

But maybe we should be looking forward instead.

In the nine years since I took a buyout from the Washington Post, I’ve seen a lot of inspiring journalism and a promising new bent toward more collaboration in telling great stories in new ways.

I’m not the only one who noticed.

“One recurring theme in the Pew Research Center’s journalism research over the last two years has been that of newsroom collaborations,” Rick Edmonds and Amy Mitchell wrote in a December 2014 Pew report titled, “Newsroom Partnerships.”

The European Press Prize, created by seven foundations with strong media connections, introduced the short list for its annual Innovation Award this year by noting that all five projects involved collaboration. The selection committee “thought the greatest innovation in journalism was the rapid growth in cross-border investigations between reporters working for different but co-operating newsrooms,” it wrote. The winner was The Migrant Files, launched in August 2013 by a group of European journalists to accurately calculate and report the deaths of emigrants trying to reach refuge in Europe.

After taking many forms over the years, newsroom partnerships are growing more prevalent – and important to the industry – in the era of digital news. These partnerships often are fueled by economic necessity, a byproduct of declining advertising revenue and staff cuts, but they’re also producing innovation as partners collaborate across different media platforms.

Collaboration is “not exactly new. It’s kind of established,” said Alan D. Mutter, who teaches at the University of California at Berkeley and writes about the economics of news in his blog Reflections of a Newsosaur.

Asked about trends in collaborative journalism, Mutter noted that some news organizations well known for partnerships have been around for a while: ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom, launched early in 2008; the Investigative News Network (recently renamed the Institute for Nonprofit News) started in 2009; and the Center for Investigative Reporting (now revealnews.org) dates to the 1970s.

The three most recent jobs I’ve held since I left the Washington Post in 2006 all involved collaboration in differing measures.

At PolitiFact, where I was deputy editor, the national staff of the fact-checking website cooperated with writers and editors of state editions of PolitiFact and vice versa, sometimes simply sharing fact-checks and articles that were relevant to both audiences, but also sometimes pitching in to help with writing or editing.

At Kaiser Health News, where I worked briefly when the roll-out of Obamacare called for more hands on deck, we worked with newspapers that carried our articles (free content for them; exposure for us) and with NPR to produce articles for both radio and website audiences.

More recently I worked as a contract writer and editor with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists on a collaborative project on a scale I couldn’t have imagined until I became a part of it – a worldwide effort by more than 150 journalists in over 50 countries to investigate the activities of HSBC Private Bank (Suisse,) a subsidiary of London-based global banking Giant HSBC Holdings.

Swiss Leaks Project: Investigative Journalism on a Mass Scale

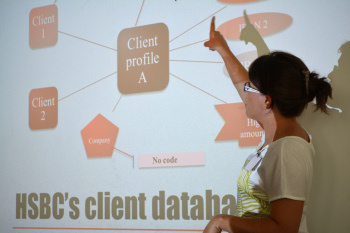

The investigation into HSBC Private Bank revolved around a large data set that a bank tech worker turned over to authorities in France several years ago. The Paris newspaper Le Monde acquired the data last year and shared it with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, an organization with a small staff in Washington and New York that coordinates investigative reporting projects around the world. ICIJ’s international data team, with members in Spain, Costa Rica, Washington and Venezuela, essentially rebuilt the information to make it easy for media partners the world over to search for information of interest to their audiences.

That data turned out to be a gold mine for investigative journalists, who analyzed it to report stories about how the private Swiss bank had helped shelter money linked to a range of illegal activity, including arms deals, blood diamond trafficking and tax evasion. The data revealed the bank had looked past evidence of law-breaking to accommodate the financial needs of customers including drug cartels and some who were wanted by Interpol.

ICIJ convened a meeting of journalists from 25 countries in Paris in September 2014 to discuss the HSBC financial data files.

Among the stories reported by the many news organizations that partnered with ICIJ (which published its own report on its website):

· The Guardian, in London, singled out bank customers who had evaded their British tax obligations; it also carried stories about Lord Stephen Green, chairman of HSBC between 2006 and 2010, and calls for the resignation of Rona Fairhead, the chairman of the BBC’s governing body, who was chair of HSBC’s audit committee until 2010 and later led the bank’s risk committee.

· Spanish partner El Confidencial took after tax evasion by the Botin family, which controls Banco Santander.

· In Belgium, journalists turned the spotlight on HSBC’s diamond-dealing clients.

· And in Zimbabwe and Tunisia, reporters highlighted the bank’s relationship with politicians and businessmen who have appeared on international sanctions’ lists or who face criminal charges.

· In Paraguay, journalists went right to the top and revealed details about the controversial financial past of the country’s serving president, Horacio Cartes.

Even after the story broke, the project attracted new partners, including Pierre Portelli and his team from The Malta Independent, whose reporting highlighted a former minister who used the Swiss private bank to hide $3.2 million from tax authorities. (Full disclosure: I am now working as a contractor with ICIJ on another project.)

Multiplatform Partnership: TV Channel Teams with Internet Site

Shortly after I finished my first contract with ICIJ, I came across an excellent piece of collaborative journalism produced by Inside Climate News and the Weather Channel, funded by the Nation Institute’s Investigative Fund. The idea for the project came from Susan White, then executive editor at Inside Climate News, a nonprofit Internet site covering energy and environmental topics.

“Susan was sort of the straw that stirred the drink, as she was with so many things,” said Marcus Stern, one of the two reporters who wrote “Boom: North America’s Explosive Oil-by-Rail Problem.”

The joint project started as a look at the oil pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, then shifted to a more dramatic story that was beginning to unfold – the dangers of shipping highly volatile crude oil in old railroad tank cars that had been designed to carry less hazardous cargo. A train hauling 2 million gallons of crude oil from North Dakota had exploded in the Canadian town of Lac-Megantic, killing 47 people in summer 2013. Three-and-a-half years later and after three more tankers had exploded in the U.S., “the effort to draft new safety regulations has been bogged down in disputes between the railroads and the oil industry over who will bear the brunt of the costs,” Stern and Sebastian Jones reported.

Stern and Jones, who had worked together at ProPublica, wrote a chillingly detailed account of the potential dangers posed by exploding oil trains. The Weather Channel produced a gripping documentary full of exploding fireballs, shouts of horror and townspeople later recounting the human costs in Lac-Megantic. Together they tell a frighteningly important story and warn that it could easily be repeated.

“I am nobody in front of the people of USA,” a young woman named Karine Blanchette tells the Weather Channel, after she has described the devastation of the Canadian town. “But I am someone who lived this tragedy – the nightmare you don’t want to see.”

“As we were putting the documentary together, we would post various cuts as we did them, and Susan sent us drafts,” said Gregory Gilderman, who produced the documentary for the Weather Channel. Harkening to earlier attitudes, he said, “You’re a print reporter, and you’re not allowed to give an opinion on a documentary. There was none of that.”

“The collaborative opportunities are there, which is great, because there are so many niche skills that are needed,” said Stern, who shared the 2006 Pulitzer Prize and George Polk Award for his role in breaking the story of former Rep. Randy “Duke” Cunningham’s corruption.

The evolution of journalism into multimedia and multiplatform story telling often calls for more skills than an individual journalist might have. In this case, Stern brought his investigative skills to the table, the Weather Channel its documentary skills, and Stern’s collaborator Jones helped find grant money to make it possible. As is often the case in journalism today, it wasn’t a lot of money. “My financial needs are not so great at this point in my career,” Stern said. More importantly, “I developed a real passion for the story.”

Gilderman said that working with other news organizations has made him want to do more. The Weather Channel (now facing financial pressures of its own) partnered with Telemundo in 2014 to produce a documentary called “The Real Death Valley” – which won the Polk Award – about migrants who made it across the border from Mexico into Texas, but wound up dying in Brooks County, where they faced drought, heat and tough terrain. Each organization told the story from its own perspective, north and south of the border, Gilderman said.

The landscape of collaborative journalism is vast and varied, and I won’t attempt to describe it all. It ranges from newspapers sharing their stories with other newspapers to provide more coverage at lower cost – the Washington Post and the Baltimore Sun swapping sports coverage, for instance – to nearby daily and statewide networks of newspapers sharing news stories to save costs. It also includes non-profits like ProPublica turning out vast amounts of excellent journalism and providing it free of charge to a variety of partners (and also collaboratively showcasing great work by others in its newsfeed, “MuckReads”).

In Ohio, eight news organizations share news on a daily basis through a partnership called the Ohio News Organization, said Columbus-Dispatch editor Benjamin J. Marrison. That sharing “allows us to focus more locally and strategically,” he said. “We can extend our resources while still providing top-quality journalism to our readers. We all don’t need to cover Ohio State playing at Nebraska – but we can if we want to. We can send a reporter to Cleveland to work on enterprise and use Cleveland’s or Akron’s game coverage.”

Members of the organization also have done joint-reporting projects on such topics as H1N1 and the state pension systems. “We customized our reports so we could lead with and focus on local angles, but we didn’t each need to do the major data analysis,” Marrison said. “We share interactive graphics and images – even the logo and illustrations.” The Cleveland Plain-Dealer used the mainbar written by the Columbus-Dispatch, supplemented with reporting from one of its own reporters.

Marrison said there are no requirements for what each news organization does. That decision remains in individual newsrooms. “But we get along and trust each other. It’s the only way to make it work.”

When Does Cooperation Stifle Competition?

Television stations are doing a version of the same thing, but in some cases it has moved from collaboration to something more like co-opting.

A 2013 report from the Pew Research Center on sharing in local TV news found that fewer stations are originating local news. “Fully a quarter of the 952 U.S. television stations that currently air local newscasts do not produce the programs themselves; another station provides them,” it said, citing research done by Bob Papper published in 2013 for the Radio Television Digital News Association.

Some media executives question whether TV stations should share newscasts.

“I think mostly in the cases of newspapers, it makes sense to me,” said Washington Post Vice President at Large Leonard Downie Jr., who led the paper during a time when it won a record 25 Pulitzer Prizes. Downie is now the Weil Family Professor of Journalism at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University. Downie leads a collaborative venture called News21, part of the Carnegie-Knight Initiative on the Future of Journalism Education, which brings top journalism students from around the country together to work on news projects.

A collaboration such as that in Ohio “doesn’t hurt coverage at all. It enhances it,” Downie said. “But where televisions stations share newscasts, that doesn’t sound very good to me for the viewer.”

In most cases, though, collaboration need not come at the expense of competition, said Eric Newton, a veteran journalist who is now senior adviser to the president of the Knight Foundation. A former managing editor of the Newseum, Newton held editing jobs at the Oakland Tribune and helped that newspaper win multiple prizes, including the Pulitzer.

Because of the huge diversity of news sources, “competition could be anybody at any moment,” Newton said. “That means we have to be better than we were. We have to find things that can’t be found by people other than us, and sometimes it’s very hard, and we have to pull together.”

Data Mining Requires Special Skills, Teamwork

One of the tasks for which collaboration may be particularly useful (besides telling stories in the multiple formats now required) is making sense out of masses of data. Sometimes organizations like ICIJ have their own data team working with large numbers of partners across platforms to mine it for news. Other times, newspapers have done their own valuable data research and then offered it to other news organizations to use.

In 2013, for instance, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel requested newborn screening data from every state and the District of Columbia. It used it as the basis for its own prize-winning story about how delays in screening put babies at risk, then published the data and made it searchable by the public. About two dozen other news organizations used the same data in their own stories.

“A lot of the time I was simply explaining the data to another reporter – making sure they understood the methodology for the analysis, and making sure they worded things correctly, like what “late” meant,” said Ellen Gabler, the reporter. “I had a ‘methodology’ box with the project, but it was still important to make sure they understood everything. Another example – some states only tracked if samples were six or more days late. So that was important for the local reporters to understand, since other places tracked at five days.”

“Some state health departments had refused to release data, and so reporters reported on that, which was excellent!” she said in an email. ”While our story created change in hospitals and health departments nationwide, it was great when other newspapers reported on the issue because people in those communities are obviously a lot more dialed into their local media outlet vs. the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. And the local reporters were able to look at prominent hospitals in their communities and talk to their own health department officials.”

The ability news organizations now have to analyze data on their own is exciting and beats relying on someone else’s analysis, Berkeley’s Mutter said. But maybe in this world of collaboration, not every news organization needs to have its own data team. “Why not have a swat squad of data quants that could do analysis” to help a newspaper in St. Louis or Switzerland, he suggested. “If you had people who were expert in this, even if they didn’t know how to parse Supreme Court decisions, they could help you do data journalism.”

And Mutter even sees a potential payoff. “If the media really had a lot of improved data proficiency, it would not only improve journalism, they could also identify data that is interesting to advertiser and marketers.”

Ah, yes. Economic survival. Still the conundrum.

But there are stories that you can’t find just anywhere. And there are journalists who are driven to find them. And there are readers who value them. So maybe that will come.

The times are “both very scary and very exciting,” Downie said. “It’s not a good time for job protection, but for the public and for journalists who are able to engage in this, it’s very exciting.”

“This duality of ‘journalism is going to hell’ and people saying ‘journalism is exciting’ goes back hundreds of years,” said the Knight Foundation’s Newton. The publishers Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst once looked like the ruination of journalism, he said. “Radio was going to ruin it. Somehow it gets ruined on a daily basis and gets up and does amazing things.”

“Like Hodding Carter [legendary Mississippi journalist Hodding Carter III] said, ‘This is the most exciting time ever to be a journalist – if you are not in search of the past.’”