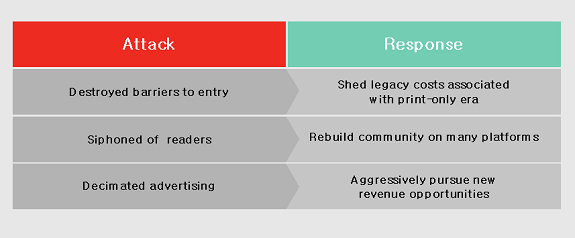

The Internet has attacked the traditional community newspaper in three different ways: disrupting costs, customer base and revenues.

Penelope Muse Abernathy

But many newspapers have incorrectly convinced themselves that they can counter the Internet’s highly disruptive power with only minor adjustments, Penelope Muse Abernathy writes in her new book, “Saving Community Journalism: The Path to Profitability.”

Abernathy, Knight chair in journalism and digital media economics at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, contends that newspapers should respond with a three-pronged approach that sheds legacy costs while building a multi-platform community with audiences and aggressively pursuing new revenue.

The basic response that many newspapers take is simply to cut costs, Abernathy said in a telephone interview. But laying off employees and reducing content in the paper fails to create the “virtuous cycle” that Abernathy recommends—a process her book describes as one in which funds are “reinvested in building audience and community in the digital edition.”

“If you just control costs you’re not building your future, you’re not rebuilding, and you are going to be stuck with diminishing revenue,” Abernathy said.

Three-pronged strategy for saving community newspapers. (Source: Penny Abernathy.)

Newspapers can cost cut in creative ways, such as by outsourcing printing services as the Rutland Herald did in Vermont, or by limiting the amount of days the newspaper is published, like the Times-Picayune has done in New Orleans. Those cost-saving measures lay the foundation for the other two strategies in her three-pronged approach.

Related story: “Book Excerpt: Saving Community Journalism”

Abernathy notes that it’s important newspapers don’t dilute an important asset they already have while cutting costs — the exceptional loyalty of their readers. Yet it is also important that community newspapers take advantage of how “hot” and “interactive” the web can be.

“With the Internet our first thought was, ‘OK, we’ll just dump the newspaper up there,’” Abernathy said. “What it totally misses from an editorial standpoint is the fact that it’s a very interactive medium.”

Many local newspapers have done a good job of building community in their print editions by including things like special sections to speak to the many interests of their audiences. Abernathy writes that UNC researchers determined that what’s most important to local readers is that the newspaper is “the most credible and comprehensive source of news and information” they care about.

But simply pushing print content to a website falls short of delivering this same community-building value to online audiences.

Abernathy said the Internet allows news outlets to take advantage of its inherent interconnectedness to supplement the print edition. News outlets need to develop content that speaks to readers’ passions and interests in a geographic region, and that connects various communities. Abernathy contends that by repositioning themselves as a multi-platform medium, newspapers can help local advertisers increase their reach and effectiveness by combining ad placements across media types.

Without building a community across multiple platforms, Abernathy believes it will be more difficult to aggressively pursue new revenue, because online advertising revenue is highly dependent on being able to give advertisers a detailed profile of audiences and show how engaged they are on the publishers’ platform. So far, newspapers have developed very little authority in setting their rates for online advertising.

The “rate problem,” Abernathy writes, is a relic of the dot-com era wherein search engines held all the power in setting advertising rates. Websites would focus their advertising to “attract eyeballs” and “build traffic,” and newspapers would follow suit and be forced to swallow the lower advertising rates in a highly competitive pool.

“The problem really is that because newspapers had no experience in terms of setting rates other than the print rate, the rate for online advertising was basically set by your huge search giants,” Abernathy said.

With an engaged audience and a community built up across platforms, Abernathy said community newspapers will be better equipped to prepare their advertising reps to tell the stories of their readers. And with a broader picture of who their audience is, advertisers should be more willing to pay more to engage that audience, allowing newspapers to reverse their “rate problem.”

“What the newspapers really need to be basing the rate on is the loyalty and engagement of what they have of their customers,” Abernathy said.

Abernathy believes it’s paramount for newspapers to be aggressive in pursuing new revenue. Her book presents the “30 percent solution,” which dictates that newspapers should cut costs by 6 percent each year, while also adding 6 percent to their revenues. Over five years, newspapers should achieve a 30 percent change in both revenues and cuts, she writes.

Her rationale is based on the average lifespan of companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500, a financial index of large companies. That lifespan is about 16 years, leading to a 6 percent annual turnover rate for companies included in the index. Therefore, she argues that community newspapers need to transform themselves at the same rate if they want to “keep pace with the market.”

Leave a Comment