Slate’s Facebook feed is on fire.

In the first five months of 2014, Slate’s social traffic was up 333 %, according to Jeremy Stahl, a senior editor at Slate. It has doubled its social media traffic every year for the last three years.

“Our numbers are way, way up,” said Stahl.

Slate.com was even quoted in the leaked New York Times Innovation Report on the topic of social media:

“When we figured out the Facebook algorithm and that Facebook mattered more than Twitter, traffic exploded,” said Jacob Weisberg of Slate in the report.

It’s obvious Slate’s social media strategy is working, but are negativity and hate from its Facebook followers part of the price of success?

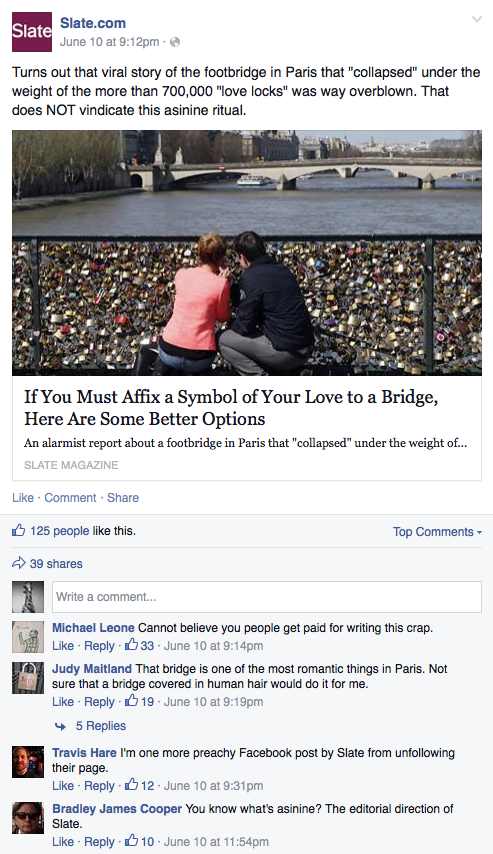

“Cannot believe you people get paid for writing this crap,” comments Michael Leone on an article about different ways to express devotion after the “Locks of Love” bridge in Paris collapsed under the weight of more than 700,000 “love locks,” padlocks attached to the bridge by lovers who throw away the key as a symbol of their commitment. The comment received 33 likes.

“This quiz is bad and you should feel bad,” comments Peter Bacon on Slate’s quiz, “What will be your song of the summer?” It was the most upvoted comment with 7 “likes.”

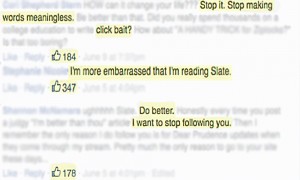

“This ziplock bag trick might (really) change your life—WATCH:” posts Slate, in reference to a way of sucking the air out of a plastic storage bag. The post causes Facebook user Cori Shepherd Stern to rant.

“HOW can it change your life???” she vents. “Stop it. Stop making words meaningless. Be better than that. Did you really spend thousands on a college education to write click bait? How about “A HANDY TRICK for Ziplocks?” Is that too boring?”

Her comment received 184 likes. Still, the original post got 831 likes and 510 shares.

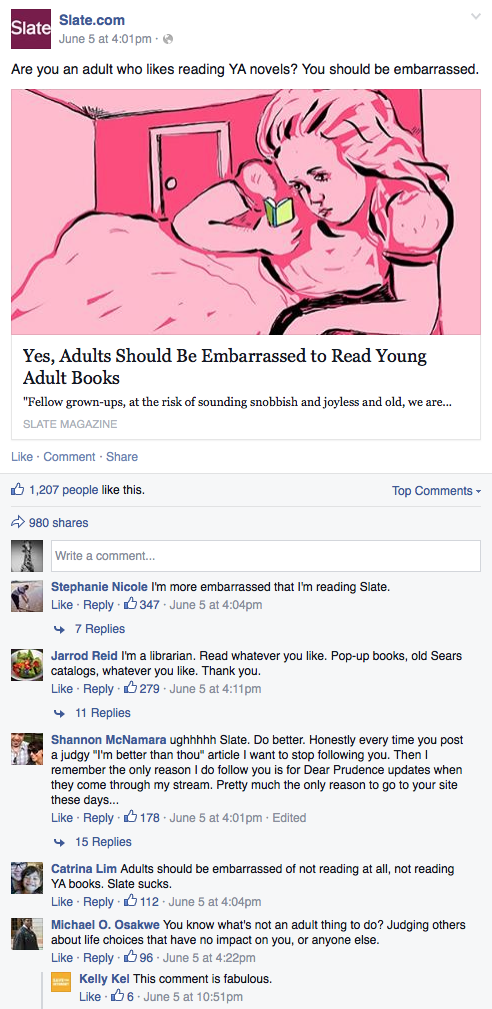

“Yes, Adults Should Be Embarrassed to Read Young Adult Books,” writes Slate, promoting another popular topic. The article itself had 1,207 likes and 979 shares.

“I’m more embarrassed that I’m reading Slate,” retorts Stephanie Nicole. Her comment garnered 347 likes.

“You know what’s not an adult thing to do?” comments Michael O. Osakwe on the same article. “Judging others about life choices that have no impact on you, or anyone else.”

It’s not just these isolated cases, either. Scrolling through Slate’s Facebook feed, negative comments can be found consistently—and they appear to often be the most “upvoted” comment of the article.

Stahl says there are always going to be trolls. Such commenters can say anything they want, he said, but at the end of the day, the numbers don’t lie: Slate’s Facebook posts are extraordinarily popular.

Still, are the commenters just hating, or are they expressing legitimate complaints? More than a few accuse Slate of posting clickbait.

“I don’t think it’s necessarily fair to categorize our posts as clickbait,” says Stahl. “We understand that a certain voice works for both Facebook and Twitter that is necessarily different from what works as a homepage headline…. Often that means a more informal and humorous voice.”

It’s apparent that this “informal and humorous voice” can infuriate people. Unfortunately, the tactics that garner the most clicks also appear to garner the most hate.

What’s even more interesting is that Slate appears to receive more negative comments on its Facebook page than notorious clickbait sites such as BuzzFeed and Upworthy. Perhaps with BuzzFeed and Upworthy, people know what to expect. Perhaps Slate is becoming a worse offender than both. But, in the end, Slate’s numbers are “up across the board,” so who cares, right?

That’s the conundrum for journalism on the web. Some of the public might hate the posts, but it’s also the public that makes the posts so popular. Slate is mixing these audience-grabbers with more deeply reported stories like this story on why Google needs satellites and drones to improve its search results and self-navigating cars, or this one about the gender gap in the obituary section of The New York Times.

Is it worth being hooked by Internet junk food to make room for stories of substance? At this stage of the game, without bait, and hate, there may be no Slate. Let the snarky comments begin.

[Editor’s Note: Jeremy Stahl’s title has been corrected to senior editor at Slate.]

Leave a Comment