They called him “Journey.” The young male gray wolf left his pack and set out on his own, traveling 1,000 miles through the Oregonian wilderness to establish a pack in California, where wild wolves haven’t been seen in almost a century. In the process, he inspired a Twitter account, two Facebook pages and a “Don’t Stop Believin’” T-shirt.

The story of Wolf OR-7 is not only romantic, it’s also a scientific anomaly. And that’s why freelance science writer Emma Marris wants to share his story. She is raising money for her project through a journalism crowdfunding platform called Beacon, planning to use Journey’s journey as the backdrop for a book on wild wolves living in the 21st century.

Marris’ project is part of a greater experiment in niche crowdfunding as media entrepreneurs and journalists collaborate to answer a few questions. Can crowdfunding help sustain journalism? If so, what kind of fundraising platforms will be required? So far, research suggests that crowdfunding has been less successful for journalism than for other types of projects, but Beacon is one of the startups trying to change that.

A Different Kind of Crowdfunding: One for All

In 2013, founders Dan Fletcher, Dmitri Cherniak and Adrian Sanders launched Beacon as a different kind of crowdfunding platform, one that focuses on writers more than their stories, and takes a collective approach by sharing revenue across different projects.

Users subscribe to their favorite of Beacon’s 150 writers for a minimum of $5 a month, and in return receive access to all the content produced by all writers on the site. About 60 percent of the subscription fee goes to the chosen writer, while the rest is shared with the other Beacon writers.

For Marris, Beacon offered a funding source for the book she was planning, where traditional publishing methods couldn’t. Typical trade book advances aren’t enough, Marris said, and she thought few journals would be interested in collaborating on her wolf research.

“I was struggling for a model for funding the research, and then I got this phone call, and this approach kind of fell into my lap,” she said.

Marris, who is based in Oregon, was one of a number of media organizations and freelance journalists that Beacon invited to participate in the platform last year.

Funding Writers, Not Stories

The idea to focus on content producers, rather than individual stories, was inspired by social media’s impact on news consumption, something Fletcher has spent his career observing. Before Beacon, he was Facebook’s managing editor, and before that he had a gig at Bloomberg, coordinating social media accounts and training.

“So much conversation about what happens in the world happens on places like Facebook and Twitter,” he said in an email interview. “If you’re able to tap into that activity, and channel it into something that actually supports journalism’s growth and development, that’s tremendously powerful.”

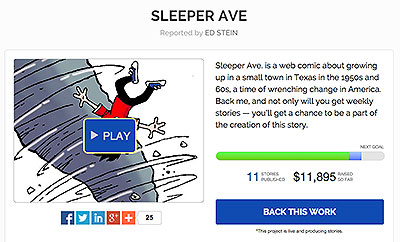

The role of the digital community is particularly helpful when it comes to niche story topics and ideas, he wrote. Former Rocky Mountain News cartoonist Ed Stein has raised nearly $12,000 on Beacon for Sleeper Ave, a webcomic based on his childhood in Texas in the 1950s and ‘60s.

But Fletcher noted Beacon is still very much a work in progress. Eighteen months, 20,000 donors and more than $1 million in raised funds after it started, Fletcher and Beacon users are still unclear on just how far this experimental system can go.

Funding Journalism Is Different: Uncertain Outcomes

The question isn’t whether donations can support journalism. That’s been well established, with NPR as a prime example, said David Cohn, who founded Spot.Us, the first journalism-specific crowdfunding platform, in 2008.

It’s also no longer whether journalists can successfully use crowdfunding on general services like Kickstarter. Shortly before Beacon’s release, Gawker raised $200,000 through an IndieGoGo campaign to purchase a video of Toronto Mayor Rob Ford smoking crack. Since then, many journalism projects have raised a lot of money on Kickstarter.

The key questions Beacon is exploring relate to whether and how niche crowdfunding platforms can help journalists advance their work.

“Crowdfunding journalism is different than raising money to build a better cooler,” Fletcher noted. “A really good story might take months to follow, and may take the writer in an unexpected direction.”

Cohn describes himself as an evangelist for media-tailored crowdfunding and believes it has strong potential, despite the fate of his own Spot.Us, which shut down in February, four years after it was acquired by American Public Media. In closing it, APM cited a list of problems, including industry shifts, staff changes and the cost of web support.

Already, journalism-specific funding platforms have shown they can offer value by providing space for publishing, a vetting process for story pitches to weed out the bad, resources for copyright and licensing, and crucial audience participation as a project progresses. But few such platforms have stuck around.

Globally focused Indie Voices no longer accepts story pitches while the company reevaluates its strategy. Emphas.is, which was for photojournalists, succumbed to financial problems after two years; and video-based Vourno is no longer live.

Two other sites, CrowdNews and Uncoverage — which received buzz from The New York Times, TechCrunch, the American Press Institute and Columbia Journalism Review — are now in limbo, having failed to secure support funds through IndieGoGo.

High Failure Rate for Journalism Crowdfunding

Following Spot.Us’s closure, the APM’s Public Insight Network commissioned a study by the University of Minnesota’s Carlson Ventures Enterprise to find out why the project and others failed.

The failure rate for journalism crowdfunding is 63 percent, versus 56 percent overall, according to the Carlson Ventures report. At Kickstarter, where the journalism project category is about to celebrate its first year, such projects have a 74.3 percent failure rate, according to company data.

While many factors can doom a startup, Cohn said niche platforms start out in a particularly precarious position that requires a balancing act. Going too broad in focus risks losing touch with the needs of journalism, he said, while going too narrow can inhibit audience growth.

Today’s media culture also doesn’t lend itself to marketing as well as other projects do, said Khari Johnson, founder of a news site called Through the Cracks: Crowdfunding in Journalism.

“There’s a wall … between revenue generation or bringing in cash, and the content,” he said. “It’s not as if journalists are taught to market themselves; we’re taught marketing is the dark side.”

Marris agreed. Though she’s raised $10,980 and published 20 stories on wolves since August, she described the process of promoting her Beacon campaign as “excruciating,” even with the help of Beacon’s marketing team.

“I was asking all these people in my life to pony up 5 bucks a month for my work, and that was very uncomfortable,” Marris said. “Think about taking your daughter to work to sell Girl Scout Cookies and multiply it by a million.”

What It Takes: Specificity, Planning and Experimentation

Despite the grim conclusions of the Spot.Us autopsy, a clearer picture is emerging of what it takes to make crowdfunding work for journalism.

As part of the Carlson Ventures Enterprise study, researchers found that a variety of factors can influence how successful a journalism crowdfunding project will be, including careful planning, specificity, relevancy and the right target audience.

In reviewing 10,227 Spot.Us donations, two other researchers discerned more about what kinds of stories readers are likely to fund. Donors preferred city infrastructure, local science and business, race issues and criminal justice to stories about media accountability, cultural diversity and education, regardless of the reporter’s age or experience.

Savanna Sturkie, a sophomore journalism student at the University of Georgia, is one of Beacon’s youngest users. Sturkie heard about Beacon from a friend’s mother and decided to give the funding platform a try for a project that showcases her travels through writing and photography.

“We live in a sharing society, so using that to create your audience in the first place is just such a good idea,” Sturkie said.

Sturkie has raised $695 so far, but said her campaign was less about financing her work, and more an effort to get exposure and observe how others are using the technology.

Marris is still skeptical about crowdfunding, at least in its current form, and wonders if it’s the right funding model for her. She said it might be helpful for bigger names — like the Huffington Post, the Texas Tribune and Techdirt, which have all had successful Beacon campaigns — but she remains ambivalent.

“Can you really build a sustainable model of funding journalism when the only people that you can get to pay for it are your friends’ moms?” Marris said.

Some campaigns on Beacon raise upward of $50,000, more than four times what the wolf project has drawn. Others are much lower, though still successful. Fletcher puts the average amount raised per project at $5,000.

In Cohn’s eyes, platforms tailor-made for media are the next branch of the journalism funding experiment. He’d like to see larger media companies create their own crowdfunding platforms to help control the media’s future.

Fletcher acknowledged that Beacon’s future forms remain unclear, and there’s more experimenting to be done.

“The future of what journalism is and how it will be supported over the next 50 years is too big for any one company,” he wrote. “It’s going to take a multitude of approaches and a love of experimentation to figure this out.”