This article summarizes a research paper presented at the 2014 Computation + Journalism Symposium. Matt Waite is a professor at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln College of Journalism and Mass Communications and founder of the Drone Journalism Lab. Ben Kreimer is a freelance journalism technologist and sUAS consultant for the Drone Journalism Lab and Kenya based African SkyCAM. See the full collection of research summaries.

By Matt Waite and Ben Kreimer

In spite of the Federal Aviation Administration’s insistence that no commercial entity can use drones without its permission, there is a thriving economy of drone videos online showing mountaineers, fancy weddings and high-dollar real estate commercials.

It doesn’t take great leaps of imagination to see how a drone might be useful in a news situation too. The videos of the damage, the photos of the crowds — it’s all right there and so tantalizingly close. But drones are not just a cheaper alternative to the news helicopter.

The real creative frontier in drone journalism is in data journalism.

To show you that, though, we had to leave the country.

Earlier this year, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Art History Professor Michael Hoff approached the Drone Journalism Lab in UNL’s College of Journalism and Mass Communications about the possibility of using drones to photograph a large archeological dig site. The dig, in southern Turkey, had unearthed some large intact Roman mosaics that were now too large to photograph safely from bucket trucks on the ground.

One of this article’s authors, Ben Kreimer, as a student, had worked as a digger at the site and knew that photographing it with a drone would be no problem. What we wondered is if we could do something more — could we map the site with a drone? Could we get enough photos of it to create a 3D photo-realistic model of a site? And, could we do that on a modern news deadline of hours instead of days?

The short answer? Yes, but not on Twitter-like-breaking news deadlines.

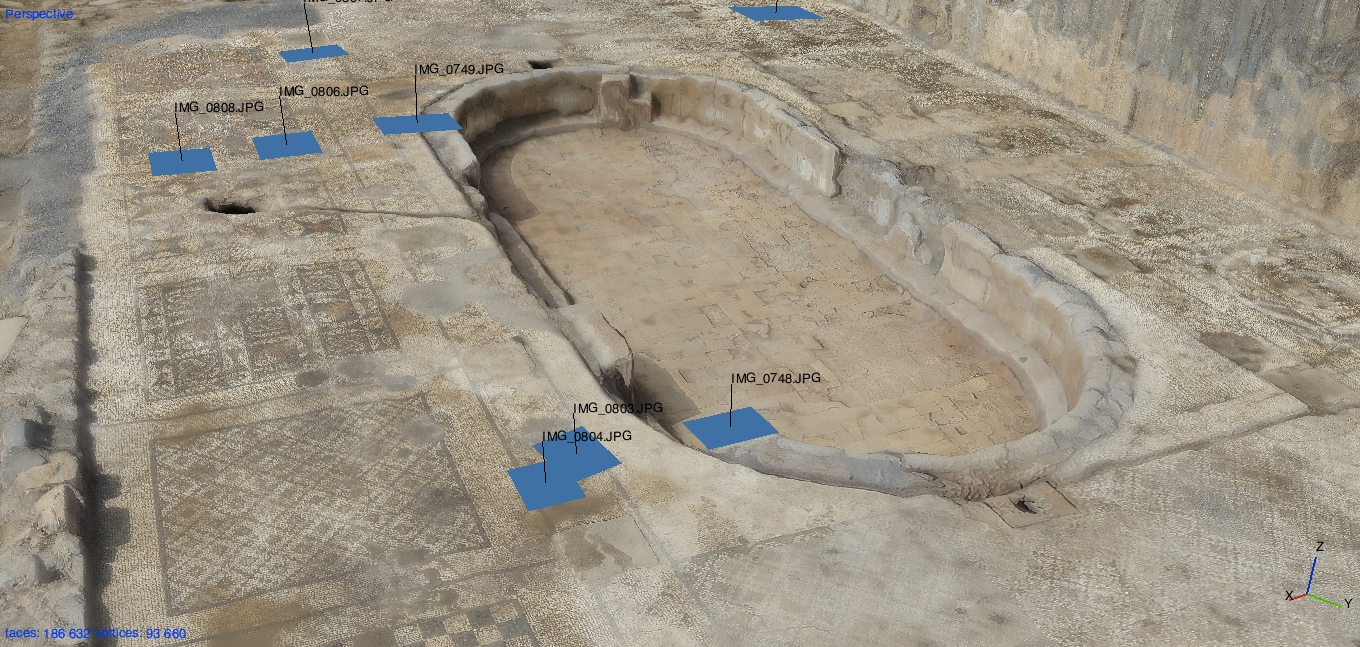

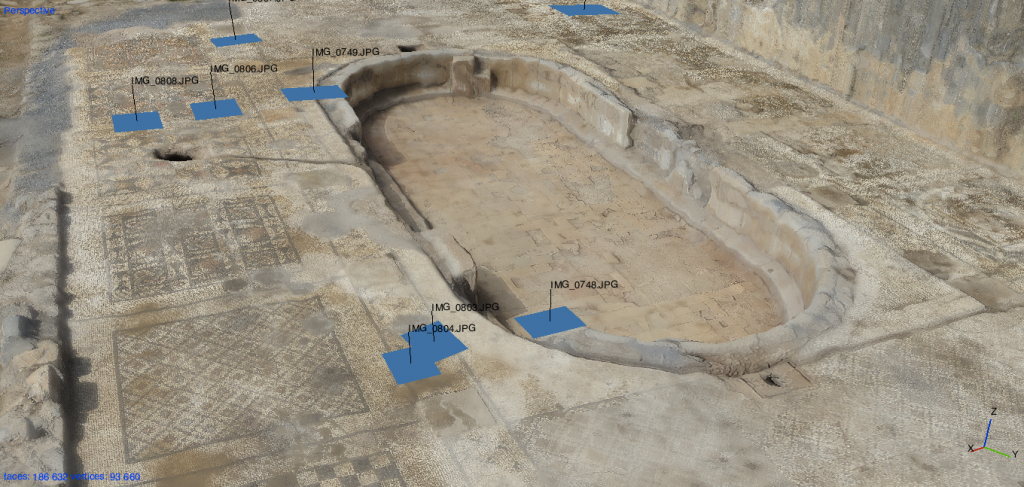

A still image of the 3D model of the archaeological site that was created from the 2,800 aerial photos captured by the drone-camera rig. The blue squares (and captions) indicate the location (and filename) of individual photos captured during the flight.

Archeology, it turns out, has a long history of using creative means to photograph sites. Manned aircraft are expensive, so cash-strapped archeologists have for centuries turned to other means to get pictures, from balloons to kites to model aircraft to, yes, drones. And, because of all of this effort into photographing sites, the archeological literature has a wealth of ideas that journalists could tap into.

The site we were invited to photograph is the location of the ancient city of Antiochia ad Cragum. It sits several hundred feet above the Mediterranean Sea on Turkey’s southern coast in the region known in antiquity as Cilicia Tracheia (Rough Cilicia). The hillsides feature steep slopes and cliffs that plummet to the sea. It’s believed the site was once an outpost for pirates until Roman general Pompey destroyed the region’s pirates in 67 A.D. Antiochos IV of Commagene founded the city in 72 A.D.

The Antiochia ad Cragum Archaeological Research Project was founded in 2005 by Hoff and Rhys Townsend, professor of art history at Clark University. Excavations have included a third-century imperial temple, possibly dedicated to Apollo, a Roman bath house, an acropolis, a colonnaded street with shops and a 1,600-square-foot Roman mosaic, considered the largest in the region. These structures are located within an area stretching over 24 hectares.

Prior to Kreimer’s arrival, Hoff received official permission to perform the drone flights from the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism’s Archaeological Directorate office.

At the site, Kreimer used a DJI Phantom 2 quad copter with a wireless telemetry system that uses an iPad Air to report location and speed, as well as provide an input interface. Onboard was a 12.1 megapixel Canon Powershot SX260 HS that has a built-in GPS chip that records the locations of each photograph. With extra batteries and other additional gear, the total cost of the kit used at the site was $3,500.

The drone-camera rig used to create the model of the dig site. A DJI Phantom 2 quad copter and a 12.1 megapixel Canon Powershot SX260 HS that has a built-in GPS chip that records the locations of each photograph. Photo courtesy of the authors.

The camera was altered using the Canon Hack Development Kit, an open source firmware package that allows developers to add features to the camera. We added an intervalometer that took a photo every two seconds. Using the Phantom’s Ground Station software, Kreimer programmed the drone to fly a pre-determined path at 25 and 45 meters altitude over portions of the site with a forward speed of 1 meter per second.

It took Kreimer about an hour to set up, plan the flights, test the paths for the needed photo overlap, fly two missions and pack up. In all, 2,800 aerial images (16.37 GB) were taken of the whole site.

But it wasn’t the flights that chewed up the time.

After the flights, Kreimer took the images from the camera and moved them to a MacBook Air with a 1.7 GHz Intel Core i7 processor, a solid-state hard drive, and 8 GB of RAM. It’s a pretty standard laptop for mobile journalists and for most applications, it’s quite fast.

Using a piece of software called PhotoScan, Kreimer then put the photos into the workflow that would turn them from individual images into a 3D model. The photos are lined up, using common elements in each frame, and then a density cloud is formed by the software, calculating object spatial characteristics based on edges and contrasts. Next Kreimer had the software create a polygonal mesh surface over the terrain’s density cloud’s points. Finally the texture layer was added, draping the three-dimensional model with lifelike surface details from the processed images.

Another view of the drone-camera rig. With extra batteries and other additional gear, the total cost of the kit used at the site was $3,500. Photo courtesy of the authors.

How long does that take? Depends on how many images you have and, we found, how much RAM you bring to the job. With only 8 GB of RAM, the models took hours to complete. A model of the mosaics and the pool they surround, from 249 aerial images, took eight hours of processing to complete.

In comparison, the model of the imperial temple and its surroundings took about 30 hours to assemble from 949 images.

To make it go faster would require balancing between computing power and input images.

Fewer images means less processing time, but it also means less detail and accuracy. If detail can’t be sacrificed, then more computing muscle needs to be brought to the site.

But, there’s a finite amount of computing power that can be crammed into a laptop, and unless you’re bringing a generator or have access to reliable power, a desktop workstation won’t be a convenient option.

A third path might be uploading the images to a cloud server that can do the processing, or to a common place where a back office could download them. But that would require time and access to broadband for upload. Remember: We’re talking about gigabytes of images, and doing that over a good 4G LTE connection in an urban area in the U.S. could take hours. In remote locations, there’s no telling what kind of access you’d have.

All that said, we did what we set out to do. Using off-the-shelf gear, we were able to build a 3D model of a location of interest in a reasonable period of time. Fast enough for breaking news? No, but quick enough to set the imagination working.

Imagine being able to make 3D models of newsworthy locations that let readers explore the site in ways not possible without being there. Imagine letting your users “walk” down storm-ravaged streets. Or explore the outside of a house or building where a newsworthy event happened.

And realize, this is just the start. Adding other sensors like LIDAR or multispectral cameras to small drones will open up huge new paths to covering issues like climate change, sea level rise and the environment.

Now if we can just get past the FAA.

Leave a Comment