This article summarizes a research paper presented at the 2014 Computation + Journalism Symposium. Eva Constantaras is a data journalism consultant at Internews. See the full collection of research summaries.

By Eva Constantaras

Developing data journalists presents a real challenge in countries with little or no history of independent media, open data or a culture of civic hacking. A lack of open information laws, bad — or no — public data and low digital literacy can make it hard to teach journalists to tell data-driven stories.

At Internews, a nonprofit that seeks to empower local media across the world, we learned that boot camps or hackathons to jumpstart data journalism in select countries almost always fell short. We first needed to grow an open data community in those countries.

In Kenya in 2013, we designed and implemented an approach to growing a data community based on a few key principles: data, demand, design and dissemination. The effort paid off when Kenyan journalists we trained used computational journalism techniques to break major investigative stories.

Filling the Void

Our first task was to accumulate enough data for journalists to tell stories relevant to their audiences. Our flagship site, the Data Dredger, is a resource for Kenyan journalists to download, embed, and publish visualizations of Kenyan data. Many exercises in the training work relied on World Bank data, but this data is hardly compelling for the average Kenyan media consumer. They want to know how many mothers die prematurely in their community as compared to another county in Kenya—not another country.

A screenshot of Data Dredger, a resource for Kenyan journalists to download, embed and publish visualizations of Kenyan data.

Gathering the data was an exercise in community building itself. Journalists, civic hackers, academics and think tanks all collaborated in identifying, scraping, cleaning and publishing data for reuse. Now, each time we publish a topic-specific series focused on pressing health challenges such as newborn deaths, malnutrition or antiretroviral coverage, journalists pick up the visualizations and data and find their own story angles. And NGOs see their data being used for a good cause.

Fostering Demand for Data

With very low levels of awareness of data among journalists, increasing data literacy became a priority over teaching the technical skills of data journalism.

Our data journalism training activities are now equally divided between developing a “data news nose” and teaching specific tools. In countries where the majority of news content involves quoting politicians with opposing opinions, developing critical thinking skills and strategies for verification of data are necessary for journalists to produce quality content. The training also helped journalists see the value in finding news angles in data instead of simply covering the day’s breaking news.

Designing a Sustainable Data Journalism Activity

To complement our online data portal, we developed an offline incubator for an open data community. A four-month fellowship took a talented group of media professionals through an intensive period of training and experimental content production for their home media outlets.

Through the fellowship we learned several important lessons:

- Learning data journalism skills takes time and commitment from trainees, their editors and publishers.

Growing relationships among journalists and the people who have data (governments, think tanks and academics) is vital to making data journalism sustainable and credible in countries that lack a robust open data policy and portal. - Online production and publication is vital for journalists during the learning process not only to practice new skills, but also to develop an online brand so that when they return to the newsroom, they are given the time and resources to produce data stories.

- Data journalism requires teamwork. Journalists, graphic designers and developers need incentives to work together on projects (reporting grants, formal partnering agreements, awards and other forms of recognition).

- The consumer should drive decisions about what format a story takes — whether it is a radio piece for a rural audience with a trusted local community radio, an interactive online visualization for a wired urban middle class or an investigative story for a print publication.

Disseminating Interactive Content

The investigations produced by our fellows were driven by the objective of the fellowship: to develop stories that enable citizens to advocate for better policies and make better decisions for their communities. Apps, visualizations and other interactive digital content were not, in themselves, the objective, but rather tools to inform public opinion.

Fellow Paul Wafula, writing for the Standard newspaper, exposed Kenya’s parliament for holding hostage the funds for a cash transfer program for the poorest Kenyans. His front-page stories uncovered missing funds, inefficient distribution and ghost recipients — going beyond the story of members of parliament fighting for a larger share of the funds to win points with their constituencies.

The government ordered an audit to identify and remove ghost recipients, developed new vetting committees that include community leaders and enlisted a mobile banking service to distribute the funding. Several agencies funding the project raised questions about why the government allowed politicians to change the original distribution plan. The government data behind his story and the international attention it garnered protected him from retaliation by politicians embarrassed by the scandal.

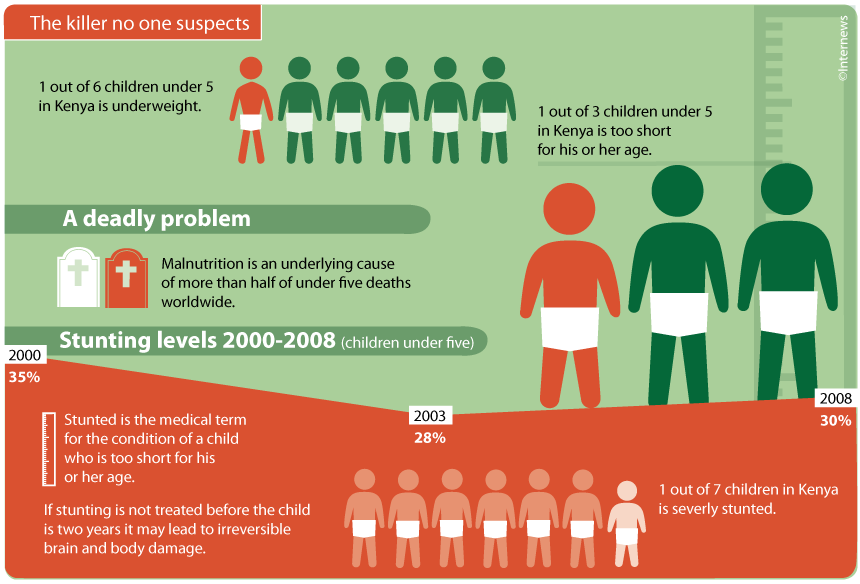

“When the Sun Sets in Turkana; Hunger Stakes and Stripes in the North,” by fellow Mercy Juma, ran on Jan. 21, 2013. The 12-minute, data-driven story is longer than any lead story anyone can remember in the history of Kenyan television. Turkana is an isolated, impoverished region of northern Kenya. Juma’s story revealed that malnutrition in children is a growing problem in Kenya, as famine becomes more intense and frequent, and that money goes to emergency food aid, not long-term drought mitigation. Due to the massive reaction to the story from individuals and organizations—whose phone calls started flooding in before the piece had finished airing, a relief fund was opened. The fund had raised Sh1.2 million ($14,000 USD) by the end of January.

The Drought Monitoring Committee requested access to her data. The committee explained that long-term drought relief strategies had been drafted but never implemented. Based on her water shortage data, the Ministry traveled to Turkana to dig more boreholes. Another agency released 2.3 billion Sh ($27 million USD) to go towards relief distribution.

An overview of all the five projects produced by the fellows, links to their stories and an explanation of their impact can be found here.

At the same time as Western media are still mired in an industry crisis and a dearth of quality international reporting, budding data journalism movements in developing countries are producing quality content. Together, there is an opportunity to fill that void and make data journalism truly global in both production and consumption.

Leave a Comment