At the start of President Barack Obama’s trip to sub-Sahara Africa this summer, Washington Post staff writer David Nakamura had about 250 followers on Instagram, a popular social media network for sharing photos and video. By the end of the week-long trip, his followers numbered more than 30,000.

A decade ago, a White House correspondent traveling with the president would have been expected only to file stories for the print edition and send breaking news updates to the web. White House pool photographers or the paper’s staff photographer provided the visuals.

But before Nakamura left for Africa in July, the Post set up a live blog for him on Instagram. In addition to writing stories, he documented the trip with his company-issued iPhone, something he routinely does now covering one of the top beats at the newspaper. (In fact, just this week, on a trip to Japan with U.S. Vice President Joe Biden, Nakamura tussled with reporters after he climbed onto a podium with his iPhone to get a better view.)

“I take so many pics now—on the tarmac with Air Force 1, aboard the Marine helo in Obama’s helocade, in the Rose Garden and even during Obama press conferences in the East room, that there’s a new question about who is a photographer and who is not,” said Nakamura, who’s been a staff writer at the paper since 1992.

Jackie Spinner teaches a smartphone photojournalism class at Columbia College Chicago. (Credit: Charles Osgood.)

He is not the only one asking the question. In news organizations around the country, reporters are increasingly providing visuals with their copy. Freelance writers are rebranding themselves as multimedia journalists, and journalism schools, conscious of where the jobs likely will be for their graduates, are training all their students to write and capture audio, photos and video.

This advent of the new Super Journalist, the photographer who writes and the writer who takes photographs, is creating one of the biggest upheavals in modern journalism since online platforms gave everyone, including monthly magazines, a 24-hour news cycle.

In this new world, a world in which everyone is a photographer, what then happens to the photojournalists?

Newsroom photographers have long been distinct and respected, if not somewhat mysterious, characters in journalism. What writer hasn’t walked by a darkroom, even a digital one, and peered in with curiosity and even some envy, feeling a bit like a band member at a football game? Good writers have always understood that the best photos make their stories memorable.

Perhaps that is why it felt so personal when the Chicago Sun-Times wiped out its entire photo staff at the end of May, axing 28 photographers and editors, including the legendary John H. White. Lindsey Bever, a summer intern for the The Guardian spoke for many in the industry when she wrote: “If Pulitzer Prize-winning photographers such as the Sun-Times’ John H. White can’t hold down a job in journalism, maybe it’s a sign that the collapse we’ve all been fearing is finally upon us.”

Related story: “Visual Journalists Are As Important As Ever”

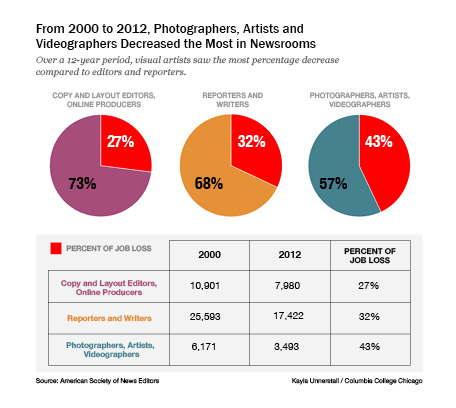

The annual newsroom census from the American Society of Newspaper Editors showed that jobs for photographers, artists and videographers fell by 43 percent, from 6,171 in 2000 to 3,493 in 2012. By comparison, the number of full-time newspaper reporters dropped by 32 percent, from 25,593 to 17,422 in the same period. Jobs for copy and layout editors and online producers fell from 10,901 to 7,980, a 27 percent loss. The Pew Research highlighted the results this month in a story about the cuts.

By Kayla Understall; Columbia College Chicago

“Fundamentally, it’s an economic issue, “ said Geneva Overholser, director of the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School of Journalism from 2008 until this year. “We feel deep regret that newsrooms are laying off professional photographers, but in so many of these dilemmas, it’s really essential to think about why we all exist. We exist because we need to fulfill the information needs of the public.”

The elimination of the entire Sun-Times photo staff certainly grabbed headlines. But it has been far from apocalyptic. Although visual journalists across American newsrooms are shrinking in numbers, only a couple of news organizations have cut their photo staffs completely, most recently, the Times-Herald in upstate New York, which laid off its four last remaining photographers at the beginning of November.

The bigger story is reporters like Mercy Quaye, who is expected to provide visual content with her company-issued smartphone for nearly every piece she writes for the 8,000-circulation Register Citizen in Torrington, Conn.

“I think having reporters provide the visuals is the most efficient way to ensure you always have interactive content for a story,” said Quaye, who covers three communities for the paper. But it also can be burdensome. “I often find myself fumbling between devices making sure I’m getting audio, video and a photo,” she added. “I think the pressure to produce visual content may cause the reporter to forget the importance of the written piece.”

While staff members at smaller newspaper have always worn multiple hats, large newsrooms that used to have the luxury to hire the best writers, the best photographers, the best copy editors and the best graphic designers are now looking for versatile reporters who can do it all. Whether such superhuman journalists already exist or can be trained to do it all—and do it well—is the source of much contention rippling through the industry.

“Anyone can get lucky with a few pictures, just like pretty much everyone has one or two dishes they’ve mastered in the kitchen,” said Brooklyn-based freelance photographer Scout Tufankjian, who has documented President Obama, the Haitian earthquake and Arab Spring. “That doesn’t mean that they can produce solid, compelling and ethically produced stories on demand. I make great hummus and kibbe. That doesn’t mean I’m capable of running a restaurant.”

Nakamura recalled an incident in 2011 after he just started on the White House beat. He was in the Rose Garden for a ceremony with the Super Bowl champs, the Green Bay Packers. He staked out a spot where he knew Obama would walk.

“Then a bunch of ‘real’ photogs came and set up their ladders right in front of me,” said Nakamura, who shoots with his iPhone. “One woman just stepped in front of me and pushed me to the side. I objected and got into a heated argument with a male photog who called me ‘just a blogger.’ I sent him the blog when I published it 20 minutes later and asked if he was published yet.”

The Value and Pitfalls of the Smartphone

The day the Sun-Times fired its photographers, Managing Editor Craig Newman announced in an email to staff that the paper would start training reporters and writers to use their iPhones to take photos, shoot video and distribute the images through social media. (In November, the newspaper agreed to bring back up to four photographers as part of a new union contract).

Jackie Spinner shows student Alex Wroblewski a smartphone photo app during a photojournalism class at Columbia College Chicago on a day when it was so cold the students’ smartphones shut off. CREDIT: Charles Osgood.

That notion, that a reporter with a phone could replace him, angered Rob Hart, a 12-year veteran of the Sun-Times. Hart started a Tumblr account when he was laid off to document his new life with an iPhone.

“It was the worst decision ever,” Hart said. “You are taking 50 percent of the equation out of the story.”

Hart said reporters and photographers approach a story differently. “The reporters crunch the numbers,” he said. “They think about the big mathematics. We think about the face. That’s what we brought to the party.”

Five months after he lost his job, Hart vacillated between anger, sadness and resolve. In a recent interview, he choked up whenever he brought up White, a professor and mentor at Columbia College Chicago before the two were colleagues at the Sun-Times. Hart now teaches photojournalism to non-photojournalism majors at Northwestern University, and he works as a freelancer, sometimes for his former competitor, the Chicago Tribune.

“The technical aspects of photography are not all that difficult,” he said. “I get 10 weeks with these kids. They’ve never shot with a camera on manual. I think after a couple of months with a camera it’s pretty easy to get down exposure and composition. But you have to spend 10 years doing it. That’s the secret to photography.”

For many photojournalists, Hart included, the problem is not the iPhone, which is merely a device, after all. The problem is that using it—or any camera, professionally requires an understanding of visual storytelling, which is about sequencing and patience, framing, knowing what to exclude as much as what to include.

Some of the most memorable images from the Boston Marathon bombing were captured by two seasoned photojournalists: Charles Krupa of the Associated Press and John Tlumacki, a staff photographer with the Boston Globe for more than 30 years.

“In many cases, whether it’s a day story or long-term project, photojournalists’ work can bring unique, audience-building content,” said Dennis Brack, a long-time designer for The Washington Post and now president of Rappahannock Media in Virginia.

As an example, Brack pointed to the Post’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 2007 investigation of the military’s Walter Reed Army Medical Center by reporters Dana Priest and Anne Hull. He noted that Priest and Hull “could have taken good pictures of their subjects with their personal cameras or smartphones.”

But those images would not have compared—and Brack is confident of this—to the work of their colleague, photographer Michel duCille, who also gained the trust of the wounded warrior subjects of the story, he said. “The audio photo galleries that resulted from duCille’s pictures and the reporting and editing of Priest and Hull resulted in hundreds of thousands of web page views,” Brack said. “In the years that have followed, of course, there have been many other examples of when great storytelling and audience engagement benefited from dedicated photo and visual staffers. It has become a cliche, but one word: ‘Snow Fall.’” (Snow Fall is a New York Times interactive story that won a Pulitzer Prize in 2013).

Many photojournalists use a smartphone (almost always an iPhone) and see it as an invaluable part of their jobs. The larger issue for photojournalists is the use of filters on apps like Hipstamatic, Instagram or Snapseed that allow the photographer to emulate film types and vintage cameras to create a certain aesthetic. In 2011, Damon Winter, a New York Times photographer, won a coveted Pictures of the Year International award for a picture story from Afghanistan that he documented using his iPhone and the Hipstamatic app. The award opened a debate among photojournalists about digital manipulation that has only intensified as reporters have started using the apps, too.

Just this month Hipstamatic released its Photojournalism SnapPak named after New York photojournalist Ben Lowy, whose iPhone image from Hurricane Sandy was the first on the cover of Time magazine in September 2012.

“At this point it seems as if anything goes, and in the end it’s up to the assigning editor who often is looking for something new and innovative,” said Joao Silva, a New York Times photographer based in South Africa. He said photojournalism itself is going through an identity crisis. At the very least, reporters who use their cameras should be aware of it.

“For my part, I am against any tool that digitally manipulates an image at source and also not a fan of excessive post production,” he said. “The camera phones are a great accessible tool for all and accepted within the realm of photojournalism but apps that filter the image should not be allowed.”

Bill Putnam, a freelance photojournalist who returned this summer after 16 months in Afghanistan, used his iPhone to document photos in the Helmand province and then posted them to his Instagram feed, using the hashtag “#LeatherneckLife.” He bought a two-pound block of aluminum with a screw-mount wide angle adapter to protect the phone. “It fit perfectly in an ammo pouch on my body armor, right next to my massive first aid pouch,” he recalled.

He said the smartphone made the people he was documenting more comfortable. He could take a picture and show it. “After a few thumbs up and heavily-accented ‘good, good,’ it wasn’t long until I was snapping away with my DSLR because they saw me, saw what I was doing and didn’t care anymore,” he said. “The iPhone, at least to me, quickly cut through all that initial relationship building every photojournalist goes through.”

But Putnam, who is now studying at American University in Washington, D.C., said the iPhone was not more important than his digital camera. “I just used it in a way that helped me break out the DSLR faster,” he said.

IPhone photo of U.S. troops entering Kuwait. By Maya Alleruzzo

Maya Alleruzzo, a photographer for the Associated Press, used her iPhone in December 2011 to document the last U.S. troops leaving Iraq and crossing into Kuwait. She was able to get a first image onto the wire within moments and stay on the scene to keep shooting.

“What I love about the iPhone is that I always have a camera with me, no matter what” said Alleruzzo, now AP’s Mideast regional photo supervisor in Cairo. “For breaking news, the most immediate images are the most valuable. These can come from our staff on the ground, citizen journalists or eyewitnesses as long as we have the moment, and we can verify the image and the facts surrounding it. But nothing replaces the quality of storytelling, in long or short form, of a photojournalist. Just as nothing replaces the insight of a reporter.”

Tufankjian said she likes the iPhone because it makes her less conspicuous and not “the weird lady with the giant loud camera.”

“It’s just a tool, just like a Leica is a tool and an SLR is a tool,” she said. “They each give you access to different images and a different look. I’ve shot stories on my iPhone that would have not worked as well on my SLR, just like I use my Leica when I need control and quality of an SLR but the subtlety and slowness of smaller, quieter camera.”

Alleruzzo said the camera should not be the focus of the conversation.

“It’s really about the eye, the heart and the brain behind that camera,” she said. “There is some really powerful storytelling being done with iPhones, by talented people with vision, with the camera they have in their hands.”

‘You Can’t Be a One-Trick Pony Anymore’

The Daily Herald, Chicago’s largest suburban newspaper, had already been rethinking how to use its photographers and writers when its competitor, the Sun-Times, cut its photo staff. Jeff Knox, the paper’s director of photography, said the paper’s editors were worried their staff and readers would think the decisions were related.

In fact, they were not, Knox said. The Daily Herald is “cross-training” both reporters and photographers by teaching photographers how to write basic stories from spot news events and teaching reporters how to shoot videos and stills, he said.

“We have a staffing shortage like anyone else and instead of having 40-something odd reporters and 19 some photographers, we want 60-some journalists,” he said. “We want to fill these gaps.”

The training is necessary, Knox said, because readers deserve quality, not just content.

“You can’t be a one-trick pony anymore,” he said. “We’re never going to be as good as a writer who’s been doing it for 10 or 15 years. They’re probably not going to take pictures like we do. But we certainly can give readers more.”

That’s why when the paper didn’t have a reporter to send to a community board meeting after a long-time village president had died, the Daily Herald dispatched a photographer to cover it. Patrick Kunzer, the night photo editor, wrote the story and took the photos that ran on the front page the next day.

“We had great pictures and a really great story we wouldn’t have had,” Knox said.

At a recent panel on the future of photography at the Chicago Photography Center, Mike Zajakowski, a picture editor for the Chicago Tribune, said there are reasons that photo departments are under scrutiny.

“Photojournalism is expensive,” he said. “The equipment costs are staggering. Doing stories right often takes time, effort and planning. Maintaining a staff of professionals is a serious commitment.”

Zajakowski said cutting photo staffs is “a disservice to the readers who understand and appreciate the value of photojournalism.”

“As many of us here know, to take a meaningful picture, pressing the shutter is only the last thing you did in a long series of actions set in motion by experience and knowledge,” he said.

Jamie Stockwell, managing editor at the San Antonio Express-News, said the Texas daily values its photo professionals even as it is asking its reporters to use their smartphones to help supplement visual content. When reporters beat a staff photographer to a crime scene or breaking news event, the paper will use those images on its website to establish its presence at the scene.

“They’ll often remain part of the online slideshows,” she said. “Reporters in bureaus also often have to take photos to be used on our inside pages, usually. For stories that are clearly Page One or major investigations, a photojournalist will join the team. We do this knowing that together, the pair can better tell deep, arresting, compelling stories that often include videos, audio slideshows and other interactive elements.”

The Charlotte Observer ran this iPhone photo taken by staff writer Theoden Janes on its front page.

Théoden Janes, pop culture writer for the Charlotte Observer, said even more than taking his own photos, there’s been a big push in his newsroom for reporters to shoot video, “short, sweet ones.”

He said the reporters have been given some training, “although the emphasis seems to be more on volume than anything else.”

Even radio reporters are producing their own photos and videos. Terri Langford, a reporter for WNYC, said she’s expected to provide visual content for every single story she produces.

“You are responsible for everything, text, radio and visual on every story,” she said. “There’s no photographer in public radio. You are the photographer. Before, in print, I’d take the occasional photo for my Twitter feed.”

Langford said training is essential. So far, she said she hasn’t been offered any.

“It’d be great if there were any training to go along with this new role I find myself in,” she said. “But there’s been none. Just any photo. That makes the web pages of public radio pretty boring visually.”

The Post’s Nakamura said the paper hasn’t offered him any training either.

“When I went to Afghanistan, the Post gave me a Canon G12 and a Flip camera, and I just sent stuff back,” he said. “In my first week there, I rushed to a suicide bombing a few blocks away and was there so quickly that I saw a leg, sheared off, on the ground right next to me. I started taking pictures of it and when I got back to our house I was full of adrenaline, and I showed the photos to my colleagues, including our former Post colleague Andrea Bruce, who is now freelancing.”

Nakamura said Bruce, an award-winning photographer, taught him a lesson he will never forget. “Uh, the Post will never run that,” he remembered her telling him. “It’s totally too gruesome for a family newspaper.” He asked her how else he could have captured the moment, and she told him to shoot the faces of people around him looking at the leg.

“I won’t forget that lesson,” he said.

Alleruzzo, who has worked more than a decade as a photographer, said one thing she’s learned is this:

“Reporters, photographers, video journalists, editors, managers and staff need to think more expansively as journalists,” she said. “Often we are living the story, and news can break wherever you are. So if a reporter is on the scene with a smartphone, great. And if a photographer is on the scene and can call in details and an eyewitness account of unfolding events, we can write the story around that and get the byline.”

Jackie Spinner (jackiespinner@mac.com) was a staff writer for the Washington Post for 14 years and covered the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan for the paper. She is the author of “Tell Them I Didn’t Cry: A Young Journalist’s Story of Joy, Loss, and Survival in Iraq.” Spinner is now an assistant professor of journalism at Columbia College Chicago and teaches smartphone photography and digital storytelling. She wrote about the closing of the foreign news bureaus in Baghdad in AJR’s April/May 2013 issue.

Leave a Comment