Journalist Nilay Patel wanted to tell the story of Indiana University shooting guard Victor Oladipo in the moments leading up the 2013 NBA draft, but didn’t want to get in the way.

So he asked the 21-year-old to record his day through Google Glass, a pair of Internet-connected spectacles with a built-in computer and video camera.

Through Glass’s viewfinder, Patel hoped to capture Oladipo’s story with a sort of “first-person experiential journalism” that he had never tried before. The results, published in a technology and culture website called The Verge, allowed Patel to convey candid moments from what he called an “extraordinary person” just hours before he became the NBA’s No. 2 overall pick.

“Getting him raw in a hotel bathroom singing Usher to himself is incredible,” said Patel, managing editor of The Verge.

The experiment was not without its disappointments, as NBA officials asked Oladipo to remove his glasses before his selection by the Orlando Magic was announced.

Patel and The Verge are among a small group of journalists and news outlets exploring the potential for Google Glass in storytelling. Their early experiments suggest that Glass and other wearable computers may have a bright future in journalism, even though the devices are far from mainstream.

“I’m more excited about the potential than what it is now,” said Robert Hernandez, an assistant professor of professional practice at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

See Hernandez talk about using Google Glass on video: “I Am A Google Glass Explorer”

So far, much of the excitement over hands-free computing devices like Glass revolves around potential uses beyond journalism – in medicine and emergency management, for example. Glass has obvious benefits for people with disabilities who can’t use their hands to operate a computer, and for surgeons who want to access information during a procedure.

But the ability to record video and take photos without using hands also has intrigued journalists, who are eager to see if Glass might allow them to construct new kinds of narratives.

Journalists testing the technology say that as it stands now, Glass best lends itself to point-of-view video shots that would be difficult to get with a regular camera. It also works well for first-person experiential stories, and for grabbing candid photos and video during stressful events such as riots. Users say Glass offers useful social media capabilities, too, which could give journalists new ways to connect with their sources and audiences.

How it Works: A Magical Floating Screen

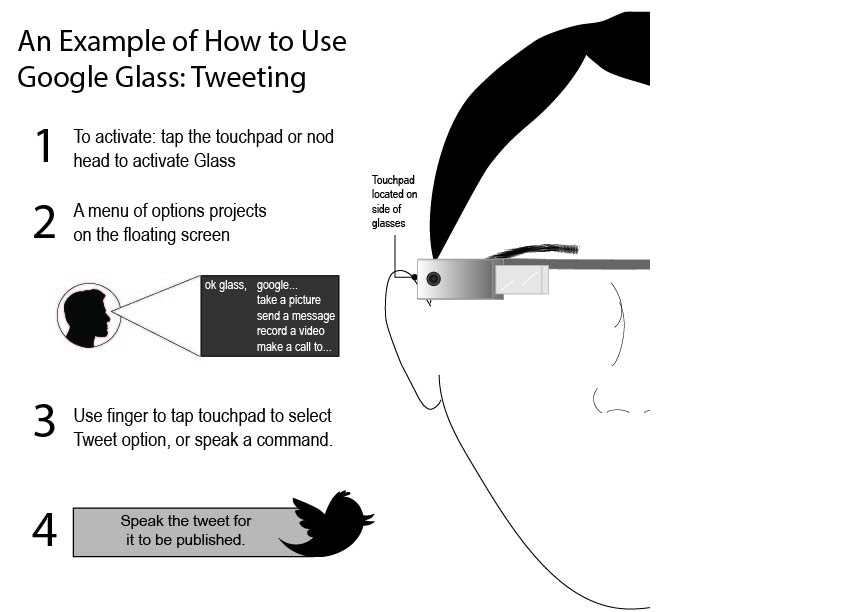

Google Glass is a small, wearable computer that resembles a pair of glasses but without the actual glass lenses. Instead, a small rectangular prism (or cube) rests in on the frame, just above the right eye, and projects a screen that allows people wearing the device to do hands-free computing–record video, say, or look up information– simply by speaking a command. “When you activate the screen it looks a lot like a 25 inch color TV floating about eight feet in front of you,” according to Google.

Users control the device through voice commands or by swiping a touchpad on the side of the glasses. When it’s turned on, either through a tap of the finger or a nod of the head, a menu appears in the small floating screen, which the user navigates by speaking or tapping the touchpad. Glass connects to the Internet using wi-fi, or connects to the user’s cell phone via Bluetooth for making calls, sending text messages and getting directions.

Right now, Google Glass is in the hands of about 10,000 people who have agreed to buy and test it at a price tag of $1,500.

A Google spokesperson said via email the company is aiming for a 2014 product launch. Company officials are not yet releasing how much the device will cost when it is released to the general public.

Tear Gas and the Glass Hacker

For journalism, perhaps the most dramatic impact of Glass and similar wearable computers will be how they enable reporters and ordinary citizens to snap photos of significant events while under duress.

Tim Pool, a producer at Vice, a global youth media company which bills itself as a leader in publishing web video, has gained notoriety for using Google Glass to capture images of world conflicts, such as the anti-government protests in Istanbul.

Pool said he has also “hacked into Glass” to enable it to have livestreaming capabilities and let him experiment with instant broadcasts of what he sees through his viewfinder.

The glasses help him record amid tough reporting situations, he said.

“If I have to run and jump over something, if I have to put my hands up to block something, I don’t have to worry about a camera,” he said. “I could also carry a DSLR. I could shoot high definition, while also live reporting to the globe.”

He says Glass is helpful in other situations, too, such as if he’s tear gassed in a riot and needs his hands to rub a lemon over his face to scrub away the effects of the gas.

Glass lets him keep recording.

“Being focused on the event is pretty important for staying safe,” he said. “I find myself climbing a lot. Climbing over walls. I need my hands.”

‘Much Deeper Level of Interaction’

Sarah Hill, a former television anchor at KOMU-TV in Missouri, uses Google Glass to tell stories of U.S. war veterans and their families for the company Veterans United.

She uses Google Glass this way: She asks a bedridden war veteran to open up a Google Hangout on his or her laptop. She joins the hangout from somewhere else, showing the veteran the view she is seeing through her Google glasses.

And then she shows a war memorial the veteran might otherwise never have seen.

“It’s a much deeper level of interaction than just watching a DVD,” she said. “With this, they have the ability to have a first-person view from my eyes. They have the ability to say, ‘Bring me closer to the waves. What’s that quote? Can you touch that granite monument and tell me what it feels like? Is that the wind blowing through a flag at Pearl Harbor?’”

“Journalists need to be figuring out this technology,” Hill said. “It’s a broadcast tower for your face. ….It’s like a global magic carpet, reducing the physical place between us, around the world.”

‘It’s the ambient video all around us that we are not getting.’

A lot of early footage coming from journalists using Glass involves point-of view-shots, providing a direct perspective that makes viewers feel like they are in the middle of an event and experiencing it, rather than watching it through a screen.

Taylor Baucom, a graduate journalism student at Syracuse University, recently used Glass to record students at a concert and published the dreamy montage on Newhouse.com, a student news service that covers the university.

Getting those shots from the point of view of a student in the middle of a concert would have been difficult with another camera, said Dan Pacheco, a Glass tester who teaches journalism and innovation at the Newhouse School of Public Communication at Syracuse University.

“It’s the ambient video all around us that we are not getting,” he said. “If you have a camera on your head and in one tap, you can capture something, that’s where Google Glass is adding a lot of value to video and photo stories we see published.”

Some note that GoPro, a camera you can strap to your head, also can record point-of-view video. Patel sees a key difference. Because Google Glass resembles eyewear, Patel noted, people around the users often forget that it’s there.

“With GoPro, you don’t forget that it’s there,” he said.

Hernandez agrees there is value to the unique point-of-view shots that Glass can capture.

He said he particularly likes to put the glasses on the face of his child, watching footage later of the boy’s arms outstretched in front of him playing with toys, or the world whipping by him as he rides a bike.

“Not all stories lend themselves to that,” he said. “Tripods are essential to quality video production. Our bodies are not tripods.”

‘Too Many Questions’

While many early adopters wear their Google Glasses only occasionally, Robert Scoble, a Silicon Valley blogger and advocate for emerging technologies, wears his all the time (proving they hold up, even in the shower.)

“You thought I was kidding when I said I would never take them off.” – Robert Scoble, on his Google + page.

“It’s a fun and novel futuristic product I like wearing,” Scoble said in an interview last month. “I don’t know how successful it will be.”

Scoble said there are “too many other questions” about the device to be able to say it will become as ubiquitous as smartphones any time soon.

Among the unknowns he cited are exactly when Google will start selling the device to everyone — and at what price.

In its current form, Glass has its fair share of challenges.

Users say the battery life is short — only 45 minutes of shooting video before needing a recharge, for example.

There is also no easy way to create a live broadcast of video being captured through Google Glasses, according to users.

Google says on its website it is making strides on updating the device’s software so it has better web browsing, battery life and other capabilities.

In December, Google announced several new updates to the device, including the ability to “take a picture with a wink,” which Google said on its website was faster than using a voice command or the touchpad.

‘The Creep’ Factor

Because Google Glass is only in the hands of a few, early attempts to report with the technology have been bumpy.

Patel, with The Verge, covered the Indy 500 while wearing Glass and was rebuffed in his attempts to approach Sarah and Todd Palin there. They were unsure what the glasses were, he said, and wondered if Patel was seeking a product endorsement rather than an interview or picture.

Sarah Palin, pictured here at the Indy 500, declined to take a photo with journalist Nilay Patel or try on Google Glass.

What he got from that moment was what he called “a creep shot” of Sarah Palin walking past him. Even though she was in public and it was legal to take her picture, Patel said it was “very, very strange.”

“Here I am, tapping the side of my face, creep shotting Sarah Palin. … It’s a weird picture to me because it was so exactly what I was seeing.”

Some journalists testing the technology said they don’t wear it all the time, keeping it most often tucked away in suitcases or shirt pockets.

Pacheco said a colleague at Syracuse University routinely asks him to remove the glasses when he enters her office, because she says, “‘I feel like I’m naked.’”

Patel said he, too, has encountered questions on whether those wearing Glass can see through clothes (they can’t.)

Jeff Jarvis, who teaches entrepreneurial journalism at The City University of New York, compares the privacy worries around Glass to those that initially swirled around cell phones that could take pictures, pointing out the numerous instances when the devices were initially banned in locker rooms.

“The first serious discussion of legal privacy didn’t occur until 1890 [upon] the invention of the Kodak camera,” he said. “It freaked people out that they could take anyone’s picture.”

Jarvis said if anyone argues that journalists need permission to take a picture in public, such as people marching in a protest or littering in the street, that is “injurious” to the profession.

“It’s a public act,” he said. “It’s my right to take that picture. We should jealously protect that notion in journalism.”

A ‘Terminator-Style’ Future

Someday, Hernandez said he envisions Glass having the intelligence to recognize something through a viewfinder – like a restaurant — and then popping a restaurant review into the screen.

Pacheco, similarly, said Glass could “use facial recognition to identify who you’re talking to. Bring up details as you’re talking to them, Terminator-style.” It also could use GPS or image recognition to develop a “What happened here?” app, he added, informing the user of “significant events that happened in a certain place where you are.”

Pacheco sees the future of wearable computing getting “even stranger” and opening up new opportunities for journalists and storytellers.

“I’m optimistic of the whole category of wearable computing and I think it’s inevitable,” he said. “. . . I know we’re just seeing the tip of the iceberg of what’s possible.”

Editor’s note: This story was corrected to reflect that Taylor Baucom, a graduate journalism student at Syracuse University, used Glass to record students at a concert that was published on Newhouse.com, a student news service that covers the university.

Leave a Comment